Review: A Bipolar Love Story

Losing your mind in your forties and beyond isn't that rare an experience, as coping mechanisms that have served you well through the years begin to breakdown.

Memoirs have never been my thing. I've found them hard to read, especially when you need to slog through details of difficult childhoods or formative experiences that are slightly informative at best and neurotically self-centered at their worst.

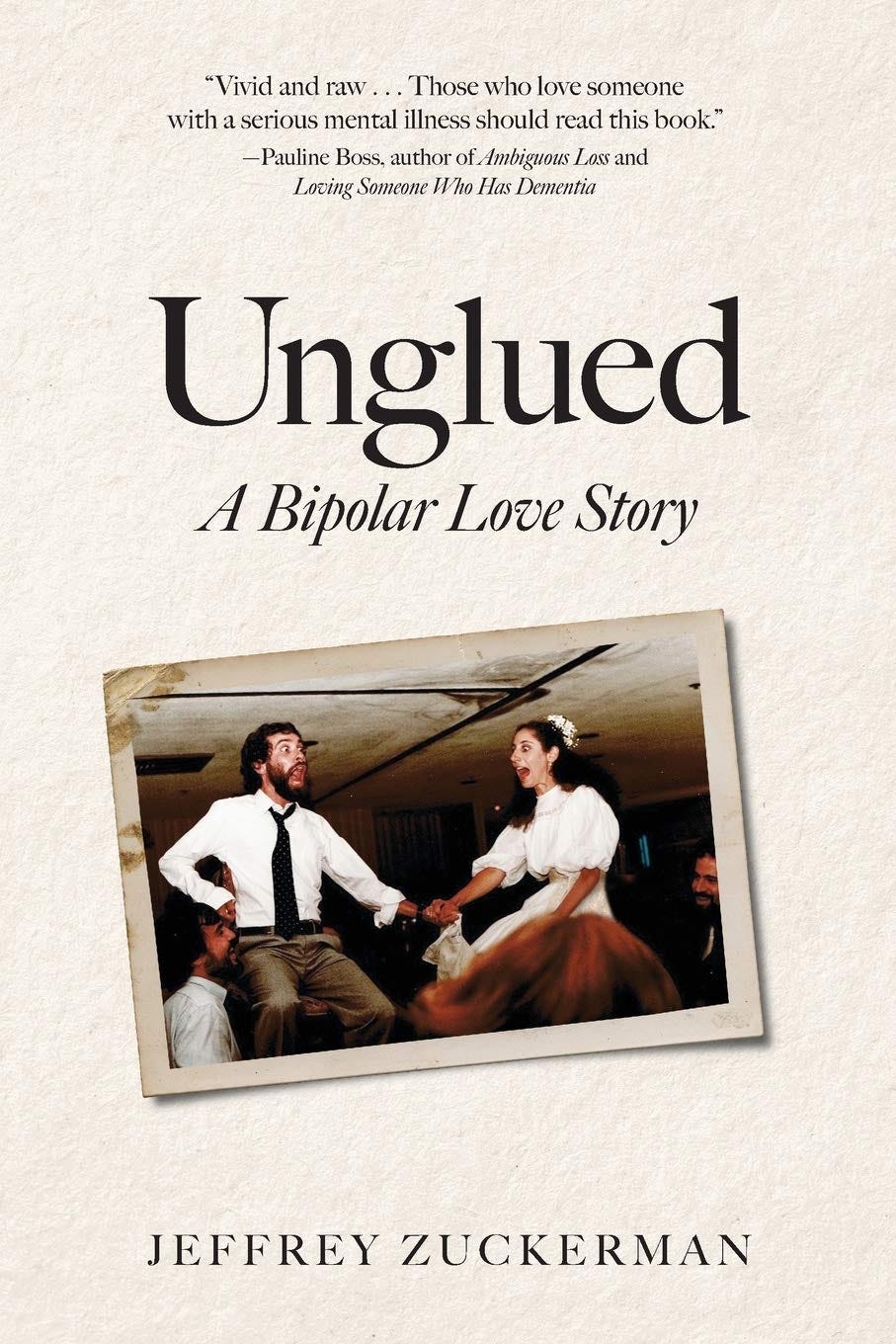

Unglued: A Bipolar Love Story by Jeff Zuckerman isn't a book I would have found on my own. Published by a company I can't find out much about on the Internet by an author who is not likely to be offered up by the Amazon algorithm, it's a bizarrely compelling and relentless self-centered narrative of what it's like to be the partner of someone dealing with a late-onset bipolar diagnosis.

Zuckerman's wife – called Leah in the book –started showing manic symptoms in her late 50s. Hitting the wall in your forties and beyond isn't that rare an experience, as coping mechanisms that have served you well through the years begin to breakdown. The distractions of a busy life ease up slightly as the pace eases.

"Leah was oblivious to her monstrous behavior," he writes. "She lacked insight, which I later learned is a measurable component of mental health illness and refers to one's cognition that something is wrong. That is what Leah lacked, all right: self-cognition. Her mind was broken."

Most manic memoirs offer a stream of stories about how someone acts when they are at their worst. Stories about mania are usually more interesting than the stories of the depressive side of manic depression because they involve things like spending tonnes of money on wildly stupid things and outlandish acts of recklessness that seemed reasonable at the time but flash big red warning lights of craziness to detached readers.

Bipolar as a spousal experience

You can get insight into what was going on in someone's mind, but you need to accept the narrator isn't a passive observer. The stories tend to focus on difficult but funny situations, incremental volatility leading to hospitalization, and the thought processes that occurred along the way. It's a delicate formula and can make for instructive reading from those suffering from the same disorder – it's oddly reassuring to hear stories that echo your own and help you realize you aren't the only person on the planet with a brain that works a certain way.

In Unglued: A Bipolar Love Story, I'm not a passive reader. I live on the other side of Zuckerman's predicament, a bipolar adult who came by his diagnosis late in life who still worries that every slight change of mood could once again derail my life.

That's probably why I felt the ache of discomfort as I made my way through the book. It's written with voice, and at times, the looseness of the humour chips away at the sympathy I might otherwise have felt as he described his fight to maintain his own sanity while trying to help his wife find hers.

An uncomfortable approach

Sometimes it's endearing. Other times it adds a level of cheek that hurts the narrative's authenticity. But this is not a bug. It's a feature. Zuckerman acknowledges his annoyance for reaching levels of frustration even he finds surprising. Leah doesn't have a borderline case – she's either full-on manic or in-bed depressed, and he's left to hold what's left of their life together. You can't blame a guy for looking for a few bright spots.

As Leah heads in for her first session of electroshock therapy, he turns his eye to the doctor's appearance.

"We met with the hospital psychiatrist, a Suzanne Somers clone, for an evaluation one week ahead of time and answers to our concerns," he wrote. "I had concerns all right, including what's up with all the gaudy makeup around your eyes?"

One of the things I complain about is that we are trying to normalize mental health conditions by sanitizing terrible diseases. Awareness campaigns centre on the need for self-care as if a warm bath and a call to a friend will cure the problems overwhelming hospitals and psych wards in countries worldwide.

Not so here. Zuckerman's decision to portray his wife as a secondary character brings clarity to the spousal experience at the expense of his wife's suffering. It feels cold and detached at times – the few moments of tenderness are far outweighed by his frustration, anger, and hopelessness.

That's not a criticism – you can see how it would be easy to stray into traditional bipolar memoir territory if he focused too much on what so many others have written so well about.

Leah’s invisible bipolar presence

Still, Leah (and lack of Leah) is a jarring presence in the book. You get tastes of her behaviour from the email and text excerpts he provides. Still, Zuckerman shows solid restraint when explaining what she may have been thinking when she hit send.

"Six hours later Leah texted me the fucking store was fucking closing, but there was a fucking problem with her fucking Target credit card," he writes. "I don't know what the deal was on the Target card. I don't know why Leah was in St. Paul in the first place and not at the Target near our home in Minneapolis."

Instead, her presence hangs over every word in the book by her actions and their effect on Zuckerman. Like Robert Pirsig in Zen And The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, he takes to the wilderness to think about what it all means when things get to be too much (spoiler: mental health crises don't offer up many answers to these sort of questions).

He couch surfs, visits friends that live far, far away as he tries to work out how to keep loving someone who isn't giving you many reasons to stick around.

"Unusual behaviour tends to produce estrangement in others which tends to further the unusual behaviour and thus the estrangement in self-stoking cycles until some sort of climax is reached," Pirsig wrote in his treaty on mental health and meaning.

Zuckerman would disagree. His life seems to have stabilized by the time his editor finally cuts him off, but there's an alarming lack of closure in any tale of mental health. Drugs continue to improve, therapists get slightly better at their jobs each day. But a disease such as bipolar is relentless. It keeps anyone in its grip looking over their shoulder worrying that every good mood is a return to mania and every down day is going to lead to crippling depression.

"In short, Leah is the thriving embodiment of why those of us living with a person living with mental illness continue to hope for a better future in a realistic way," he writes.

Speaking for those of us on the crazy side of the ledger, we hope so too.